A photo documentary on coffee cultivation in Brazil

- Page 2 -

|

|

The Coffee Fruit ('O fruto do café') After the flowering, the cherries of the Arabica Coffee in this region have a maturing period of 6 to 8 months. The Arabica fruits are a little longer and bigger than those of the Robusta Coffee. Besides, they are significantly more sensitive and susceptible to weather conditions, infestation and diseases than Robusta Coffee. The matured fruit has a red, or – according to the variety – yellow-reddish outer skin. Inside is a soft, whitish and sugary fleshy fruit, the so-called pulp (‘pulpa’). Typically, the fruits contain two seeds, the future coffee beans. Each seed is protected by a thin but solid silver membrane and both seeds are individually still enclosed in the thin beige inner layer parchment skin (‘pergaminho’). In this predominantly microclimatic region with a mild average temperature between 18° und 20ºC, the Arabica varieties mature into a high quality and full-bodied coffee. This is characterized by a certain sweetness, a fruity aroma, and a delicate acidity. |

Mechanical Harvest: With the tractor in the coffee field

Manual harvest with the sieve

|

Brazilian Terms for Different Levels of Maturity of the Coffee Fruit

The bóias are

subdivided again in two types:

|

Coffee cleaning: "Abanar o café"

The harvest machine in the field

The inside of a harvest machine

Photographed at the 'Memorial do Imigrante', São Paulo

Sunset with old farm house

Advertisement

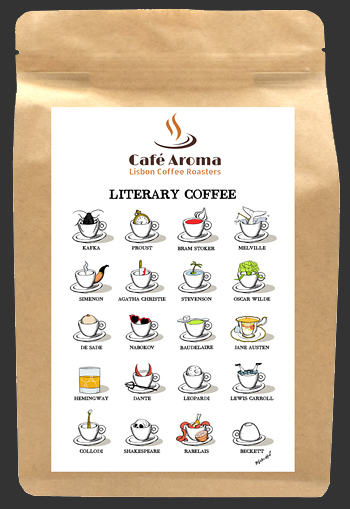

A well-balanced espresso for all literature lovers.

What goes better with a good book than a cup of coffee? (Except for a piece of cake, of course.)

Be inspired by our label, designed by the well-known Italian graphic artist Gianluca Biscalchin.

© Copyright Photographs and Texts: Jochen Weber