[Home]

|

“Teret,

Teret” – “A story, a story!” calls out the

traditional story-teller from Ethiopia, to announce the start of a new

story. “Yelam Beret. Yemeseret,” answer the excited

children and youth in a half singing rhyme, which means

“cowshed”, and “foundation or origin” (=

stories that arise out of tradition).

Thus begins a typical evening of Ethiopian story-telling tradition. This ageless tradition signifies a good time of togetherness, wherein the whole village discusses God and the world, their own identity and numerous other questions, that have occupied man since time immemorial. As the exciting narrative comes to an end, the story-teller finishes with the rhyme, “Teretayn Melesu, Afayn Bedabbo Abesu”, which means something like, “As a reward for my story, give me bread to eat.” Thereafter, someone or the other takes over the role of the story teller, and begins again with, “Teret, Teret…”, another exciting and informative story.

|

|

The

monks of the monastery had, however, heard the conversation between

Kaldi and the priest, and unable to let go off the subject, showed a

great interest in the red berries. Finally, one of them took a few

berries and chewed on them cautiously. Soon after, he felt a freshness in his body and he became just as lively, as Kaldi had narrated. That night in the monastery there should have been lengthy prayers through the night. Instead, that night, the priests who would have otherwise dozed off, lay wide awake, because they had all eaten the red berries. The priest asked one of the monks, what was going on. He told him that they all had tried the red berries. “That is a curse, this has to be the devil’s deal!” The priest threw the rest of the berries in the burning fire. Suddenly, a seductive fragrance emanated from the fumes of the fire into the air and everyone of them was enchanted by it, even the priest! |

| Much time has passed since those eventful days. The red berries that Kaldi had found were imported to several countries outside of Ethiopia, and they became popular and much loved worldwide, as a drink that one calls “Coffee”. This is the beginning of the history of coffee, which was discovered in Ethiopia.” | |

|

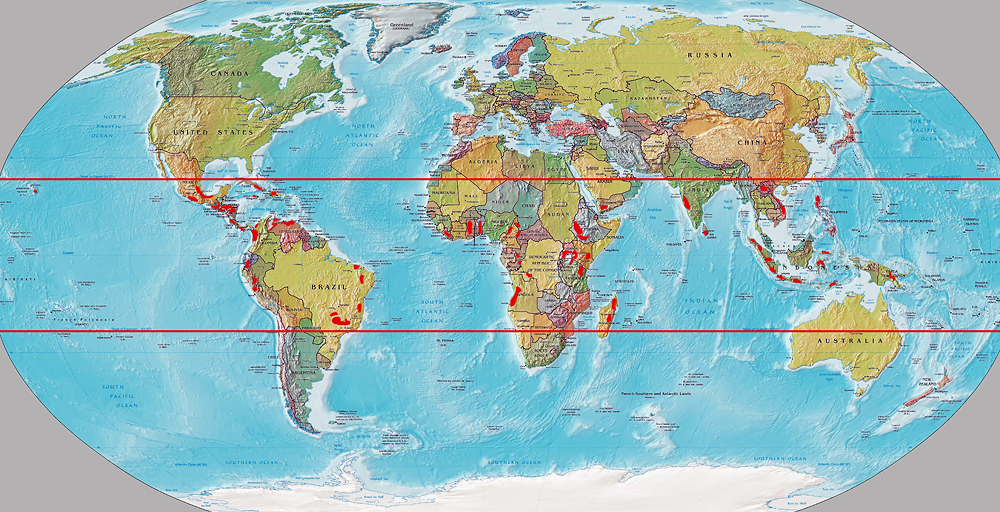

The

coffee growing in Ethiopia is 100% Arabica Coffee. Besides the

Ethiopian Arabica Coffee is the Canephora Coffee (Robusta) which comes

originally from the Congo, and the Liberica Coffee, from Liberia. These

are the three typical kinds of coffee since the time coffee was

discovered. They all originate from Africa, but the Europeans in

particular have spread the seeds of coffee across the entire world! And

that is why today, coffee is grown in Middle and South America,

Indonesia, Hawaii, Vietnam and since recently, even in China. The

Robusta and Liberica seeds, which are more resistant to diseases and

parasites grow in areas with lower altitude than Arabica Coffee and

have a higher productivity.

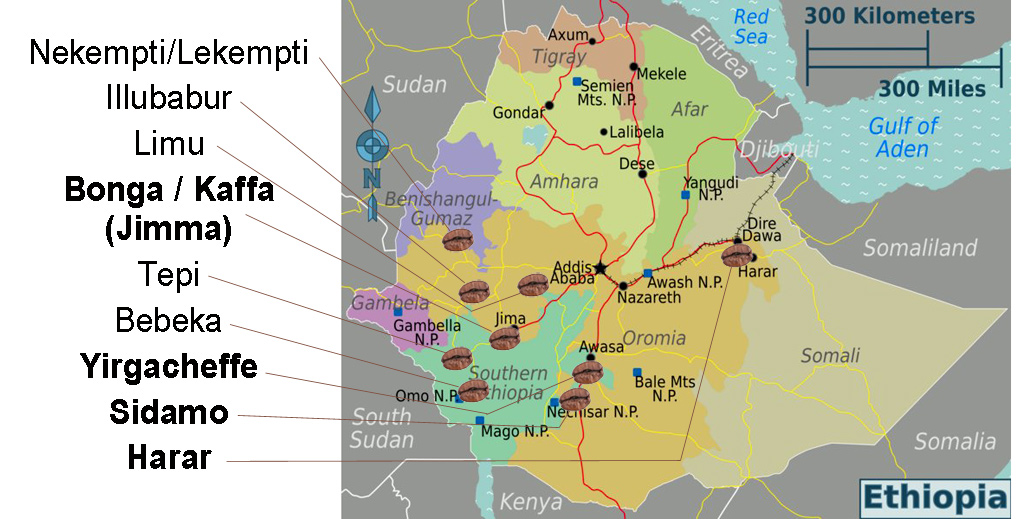

In the wild forests of South and Southwest Ethiopia the trees with wild coffee still grow in the same way man found them right at the beginning. These trees are classified as the forefathers of the present day Arabica coffee plants, which is why locally, they are worshipped as mother trees of coffee and their ownership is passed on from generation to generation. Their average height is about 2m, some, however, are 6 - 8 m high. Wild coffee trees can grow up to a height of 8m. They grow in soil that is rich and leafy, which simultaneously allows the water to drain and yet retains moisture. The altitude is about 1,100 m – 2,100 m above see level, the annual rainfall is 1,500 mm – 2,500 mm. These cloud forests are one of the most bio-diverse regions of the world. There are more than 700 types of plants including medicinal plants, about 300 species of birds as well as antelopes, buffaloes, leopards and even lions living here. Arabica Coffee belongs to the one of the few globally traded products, that still exist in their homeland in the original form as wild plants. The research from the University of Addis Ababa shows that there are about 60 genetic strains of coffee. This genetic diversity presents itself increasingly as the main focus of public interest, because these originally, wild coffees have a huge cultural importance and a greater biological value. In 1970, the cross breeding of a gene of a coffee tree from the Ethiopian forest had solved a serious problem of infestation of fungus in coffee plantations in Latin America. This had helped to prevent a grave economic crisis. The value of the legacy of this wild coffee is thus incalculable. However, the Ethiopian forests, where the wild coffee grows, is becoming smaller with every passing year. It is said that two thirds of the forests in Ethiopia are already lost and the worry is that the forests, which have been home to the wild Arabica Coffee are likely to become extinct some time or the other. To prevent this, in 2010, the Naturschutzbund Deutschland (NABU) managed to get the wild coffee forests in the region of Kaffa the recognition of UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. This Biosphere Reserve, with 760,000 hectares, is about half the size of Schleswig-Holstein in Germany. A large part of it is covered with evergreen mountain cloud forests, which houses numerous types of rare animals and plants. The forests are however, especially famous for the last reserves of Arabica Coffee. The Ethiopian Arabica seeds have, on the whole, an excellent flavour. The uniqueness of the coffee in its “home country” lies, however, also in the traditional art of the cultivation. This can be classified in the following four categories. The Forest Coffee is harvested in the wild and tropical forests of the Southwest mountainous regions of Ethiopia (Kaffa). The forest is cared for with minimum management, for example cutting off the undergrowth. The wild coffee constitutes about 5 - 6% of the entire production of Ethiopian coffee. While the forest during the forest coffee cultivation is left as is, undisturbed, during the Semi Forest Coffee cultivation, the forest is trimmed by the famers, and the wild coffee trees are actively attended to like on coffee plantations. This type of procedure for coffee takes place in general in South and Southwest Ethiopia. This coffee covers about 20% of the entire Ethiopian coffee production. The so called Garden Coffee is the most common form of cultivation among all the coffee grown in Ethiopia. The famers plant a few mostly cultivated coffee trees in their backyards, weed and hoe the soil and mulch the ground the whole year round. Garden Coffee is grown in South and East Ethiopia by small farmers. The productivity of this method of cultivation is much higher than the aforementioned methods. Plantation Coffee is grown efficiently and in a modern way on big farms. For this, the farmers use high quality, cultured seeds in their plantations, and ensure enough space between the saplings. The plantation coffee occupies a share of only 4% of the total production, but is increasing rapidly. |

|

|

Visit to the original coffee trees

Once on a day trip, I went from Addis Ababa to Bonga, a small town in the central region of Kaffa in Southwest Ethiopia. My intent was to visit the forests of the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and the German organization NABU, in which natural, wild coffee trees grow. On the way to Bonga, we passed beautiful landscapes, drove through vast expanses of pasturelands, as well as through old forest highlands, full of the Teff plant, the traditional Ethiopian staple food, from which the soft, sour flat bread, Injera is made. Bonga is a small town, in and around which many families live from coffee. There is always, everywhere in the city, a fresh roasted coffee aroma of the coffee ceremony, because coffee plays an important role in the daily life of the Ethiopian: on an average, coffee is freshly roasted and prepared three times a day or consumed in one of the numerous café-like shacks. On the edge of the wild coffee forests, the farmers have built their round huts (Tukulus), where they stay during the harvesting season from October to January. Standing in the forest between all the old, wild and original coffee trees, I experienced a sublime feeling. I was surprised at how tall the trees were, when I discovered the not-yet harvested red, ripe coffee berries towering over me. I had expected smaller coffee trees, because so far I had only known of smaller coffee trees in coffee plantations. The fruits that are not plucked simply fall on the ground. The seeds contained in them spring up as new trees again and again and the people who live here harvest those fruits anew. This has been the cycle of the wild coffee and of the village people since the time of Kaldi, the goatherd. The people unfortunately often cannot survive only from the income of the coffee. That is why, when place permits, they also farm wheat and maize. If the coffee price sinks too much, some farmers clear up the forest for new land, which likely endangers the existence of the coffee forests. I am invited for coffee by one of the coffee farmers. We sit in front of the clay hut, and farmer’s wife prepares the coffee inside – this has been women’s work since times immemorial, and girls are trained in the art of coffee preparation from the age of ten. Inside the clay hut, the woman roasts the coffee, and then crushes the warm coffee beans into a powder with a pestle. Finally, the coffee powder is cooked with water on an open flame. Then the farmer’s wife brings us from inside the clay hut a very strong, black and fuming coffee. Luckily, I am offered some sugar, as the Ethiopians also like to drink their coffee salty. The farmer next to me offers me freshly roasted barley kernels as a snack to accompany the coffee with gestures of “eating”. It goes surprisingly well with the coffee! While we drink coffee and eat kernels quietly, without talking, for the first time, I have a feeling of understanding the land and the people, better.  |

Ethiopian Coffee Ceremony |

|

Epilogue – The stories and legends of coffee

The story of Kaldi, apart from the name Kali or Kalitti, is told with three different variations. In one of the variations, as narrated in this documentary, the monks threw the coffee cherries in the fire and discovered coffee roasting at the same time. In a second variation, this part is missing; the monks try the ripe coffee berries and the roasting is discovered much later. In a third variation, Kaldi and the monks try only the leaves of the coffee trees at first and discover the coffee cherries much later, which naturally had a much stronger effect. Depending on the source, the story of the discovery of coffee dates between the 2nd century and 6th-8th centuries. The first written testimony of the story of Kaldi was written by a resident of Rome, and Lebanese linguist, Antoine Faustus Nairon, in his book, “De Saluberrima potione Cahue seu Cafe nuncupata Discurscus” in the year 1671. The legend of the Ethiopian goatherd Kaldi is the most widespread, and one is quite united in the fact that the Kaffa region in the Abyssinian Highlands in Ethiopia addressed in the legend is the original homeland of the coffee tree. However, there are still many more legends of the origin of coffee, of which I am listing for the sake of completeness, the most important. Sheikh Umar: This legend of the discovery of coffee originated in Yemen, where the Priest, Sheikh Umar had noticed the effect of the coffee fruit on birds and spread the novel news. Unfortunately, there lacks any written reference, which could have proved the veracity of this legend. Naironus Banesius: This Maronite monk, in the middle of the 17th century, had observed a herd of cattle behaving strangely. It struck him that that animals were extraordinarily lively, they did not rest till late into the night and showed absolutely no signs of fatigue. The monk found out that the animals had eaten the yellow and red berry-like fruits of a plant. The monk prepared a brew out of the fruits of this plant and realized that his fatigue disappeared and he could stay awake all night without a problem. The Prophet Mohammed: The story of the great Prophet Mohammed narrates quite a different legend. Oriental narrators report that the Archangel Gabriel appeared before the sick Prophet with a bowl of hot, dark liquid, which he called, “quawa”. After enjoying the drink, Mohammed became healthy again quickly and regained his spirit. With the help of this heavenly strength, he was able to bring together a huge Islamic empire, one that the world had hitherto never seen. The Dervish Omar: The legend that cannot be missed is that of the young Dervish (Muslim mendicant) named Omar. He was slandered, unjustly condemned and banished to a remote rocky desert along with his companions. Finally, at his wit’s end, dying of hunger and thirst, he tried the fruits of an unknown bush and cooked a brew from it. He recovered miraculously and returned to the town and told the story of the magical fruit. Now everyone wanted a taste of this fruit, and Omar was showered with honours and he even got a palace from the Caliph. The name of coffee There are different theories for the origin of the name, “Coffee”. The first is that coffee has got its name from “Kaffa”, that is from the region it was discovered. The second theory, which finds far more explanation in literature, claims that that name, which was derived partly from the Arabic original “qahwah” and partly from the Turkish form “kahveh” was adapted into the European languages in the 1600s. Although the name for this drink is recognized across many countries of the world on this basis, coffee in Amharic, the Ethiopian official language is “bunna”, in another Ethiopian language “bun”, “buna” or “bona” (but also for e.g. “kawa”). The name “bunna” for coffee was given much earlier by the caravan traders, who transported the coffee across the entire Ethiopian highlands. At the time, the traders were often invited by a local family for coffee and the woman of the house prepared coffee for them. This woman was called “genne bunno” or “genne bunne”, where “genne” means woman. To date there exists a good tradition and custom of the people of Kaffa who own the coffee plants, of sending their family and friends coffee cherries or coffee beans in a package with the inscription, “bunno-Kaffa”, which means “coffee from Kaffa”. |

Ethiopian coffee with the sweet spice “Tena Adam”  Ethiopian coffee pot “Jebena” |