Lanscape of the Chapada Diamantina |

|

|

The name Diamant is derived from the Greek words, diaphainein (diaphanous) and adamantos

(invincible). No wonder: After all, the diamond is the hardest known

natural material found on our planet! The formation of the diamond has

occurred at different times throughout the evolution process of our

planet. The youngest diamonds are about hundred odd years old; the

oldest are estimated to be about three billion years old. They are

comprised of carbon and are formed in the earth’s core under

enormously high pressure at depths of 100 to 200 kilometers and

temperatures of over 1300° C.

The volcanic rock transports shards of the earth’s core

containing diamonds on to the earth’s surface through volcanic

eruption. Through the weathering process, owing to which the hardness

of the diamonds remains intact, they are transported further and get

deposited in valleys and rivers, which is where most diamonds are found

today. But, because of the meteoritic impact, the carbon is so strongly

compromised that small diamond crystals are formed. |

|

|

Gruta Azul, Chapada Diamantina |

In

ideal conditions the diamond is transparent. However, sometimes it may

happen that it gets tarnished due to different pollutants, or in

different lighting, the colour may get stained.

There are four criteria to evaluate a diamond, the so-called “4 Cs”: carat, colour, clarity and cut.

The weight of a diamond is traditionally stated in Carats, wherein one

Carat is equivalent to 0.2 grams. The diamond is categorized in

different groups depending on its shade of white, where in the colour

starts with “extremely fine white+” (River+) and ends in

“tinted 4” (Yellow).

The purity of the diamond is evaluated through its

“clarity”. The higher the impurities or inclusions in the

diamond, the lower is the classification grade in terms of clarity. The

last evaluation criterion is the “cut”, that is the form or

cut of a diamond. |

|

|

Poço Azul, Chapada

Diamantina |

|

|

After

lunch, back again to the river: more shoveling, rinsing, sieving! The

sun shines without mercy, but it is surprising how a person can get

used to it. To begin with, Cago installs the grate once again in the

dam. Many of the garimpeiros

work in pairs and share the proceeds. However, while Cago works alone,

he must also shovel the other side of the dam to ensure a good outflow

of water and to maintain a ‘passage’ through the grate.

Once this is done, he continues to shovel the gravel into the

wheelbarrow, untiringly, the entire afternoon, ensuring that every haul

is flushed out through the grate. At the same time, he proceeds

cautiously with the grate, by no means is he rough or coarse. After

filling the wheelbarrow, he removes the bigger stones from the grate to

ensure that the water flows uninterrupted. No, he is not bored, and

neither does he feel isolated. Every now and then a colleague comes

along and they chit-chat while he continues to shovel. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

oldest diamonds come from India and were found here as early as 4000

BC! Before the discovery of the Brazilian deposits in the year 1725,

India was the only country that supplied diamonds. In 1730, the Royal

Palace of Portugal declared the discovery site of the state of Minas Gerais in the Brazilian colony, as the property of the Crown. A new fiscal source of income was - of course - always welcome!

The city of Tejuco, located to

the north of Belo Horizonte, and founded by the diamond prospectors was

later renamed as what is today known as the Diamantina.

Diamonds were discovered in Serra da Chapada in the state of Bahia in

the year 1755, and therefore it was given the name, Chapada Diamantina.

The existence of these sites can be attributed to the transfer of

weathered deposits containing diamonds borne from volcanic rocks. |

|

|

|

|

The

quality of the Brazilian diamonds can, in general, be described as

good. The only limitation being that they are, on an average, of a

smaller size.

Other than the Canadian firm “Brazilian Diamonds Ltd.”,

even the Brazilian mining firm, “Mineração Rio Novo

Ltda” is now mining underwater, partly with floating dredgers and

divers, as well as with the help of pipes and water pumps. Essentially,

however, the traditional, really archaic garimpeiro system is still maintained, even after the issuance of a law in 1989, granting concessions in the working conditions.

On Saturdays Cago walks the distance of 15 kilometers to Lençois

to shop and visit his family and friends. He would rather buy a

mountain bike, but his frugal earnings are not enough to save for it.

“The money is just enough for the bare necessities.” He is separated from his wife, and their two sons live with her.

|

|

|

|

|

|

When he is in town, he visits them regularly. He says with a friendly smile, “I always look forward to seeing them.” He visits his friends only when he has a little money to spare, not so that he can be simply invited for a beer. “I cannot turn up every time without money and allow them to endure with me. That would just not be right,” he looks at me questioningly.

Cago’s parents are retired and live in Igatù,

an old diamond-mining town, situated at a distance of about 130

kilometers from Lençois. Once in a while, time and money

permitting, he travels by bus to visit them. Despite the limitation of

materials and hard physical labour, Cago appears satisfied and

balanced. He stands firm in his life and has clear ideas. He portrays

to all, an iron will, but in reality he is cheerful and level

headed. |

|

|

|

|

|

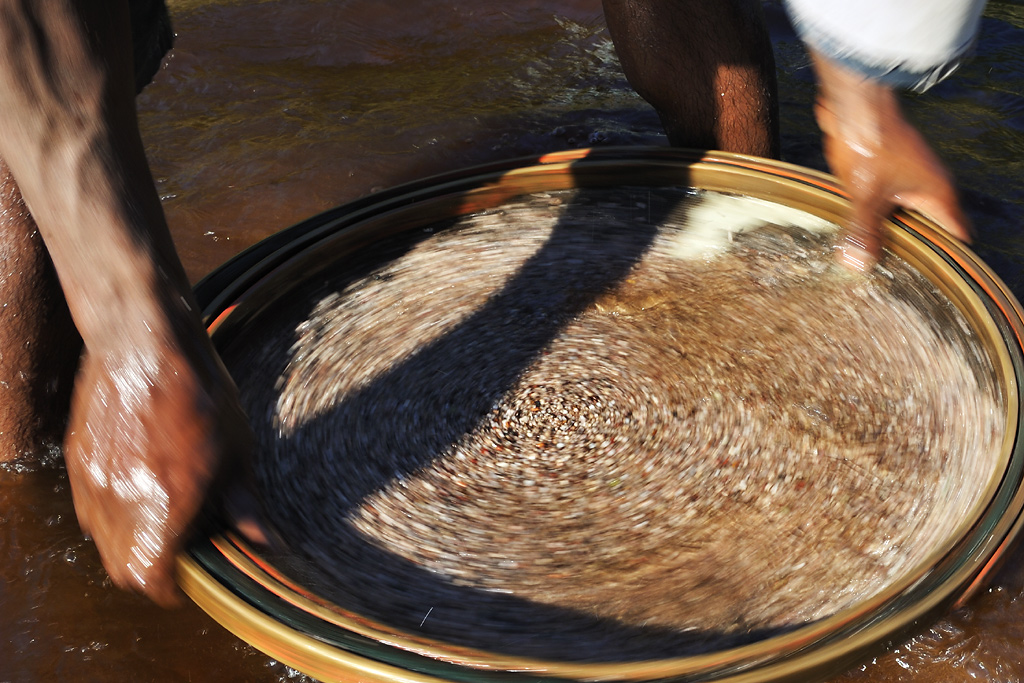

At

the end of the working day, around 17:00 hours, he starts sieving, that

is once more, he sieves the gravel out of the grate. He is excited,

placing the sieves, one on top of the other, swiveling the stones and

the sand rhythmically in circles. The sand drains through the sieve and

the heavier stones continue to rotate within. That means a diamond, if

there is one, should be lying in the middle of the sieve.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| After the long, hot and tough day, I cannot quite believe, that he would find something. Still, I ask him curious, “And?”

He looks for a while with total concentration at the remaining stones

in the last sieve and then says, much too calmly, “Tem”.

He had found one! I jump up, this I have to see! Oops, where is it? I

can’t see any diamond. Here? No there? Definitely not so easy,

there are natural crystals in there, which can deceive a novice, they

are absolutely worthless. Then he said, again too calmly, “Tem dois!” Wow! Two! Here is the first…. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Well, they are quite small.

Nevertheless, I am happy for him. But Cago remains calm, even though it

is an important find for him. What would he get for the diamonds from

his dealer? Cago examines the diamonds once again in silence and says,

“The bigger one is not

particularly beautiful; it is broken and tarnished. The smaller one is

clear and very elegant, but still very small. About 30 Reais for each,

approximately”. That is not too much and I am a little

disappointed - I would have granted him more. I thought, rough diamonds

should have been more expensive. But anyhow, this day had been

profitable for him. He had once again made the best out of the

situation and earned himself some days of freedom from the river. Parabéns, caro Cago! (Congratulations, dear Cago!) |

|

|

The End |